Large Lower Face Defect from Gunshot Wound.

History:

A 58 year old male smoker with past medical history significant for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and sleep apnea presented to the emergency department after sustaining a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the face resulting in multiple facial fractures including the maxilla, mandible, and orbital floor, as well as loss of 13cm of mandible and soft tissues of the floor of the mouth.

Findings:

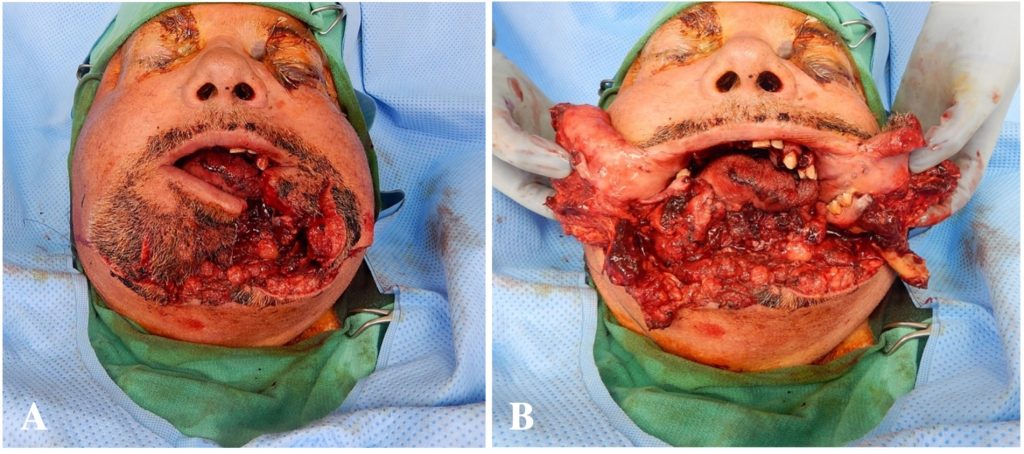

Initial exam displayed massive loss of anterior jaw and soft tissue. The patient had a large open wound to the mandible with exposure of tongue base and bony remnants, large palatal defect with maxillary comminution, and no clear exit wound, as seen below in Figure 1A-1B.

Fig. 1A – 1B.Pre-operative photos showing the extent of soft tissue and bony loss.

Diagnosis:

Extensive bilateral facial fractures with loss of central mandible, palatal injury, and tongue laceration s/p gunshot wound.

Differential Diagnoses:

Not applicable.

Workup Required:

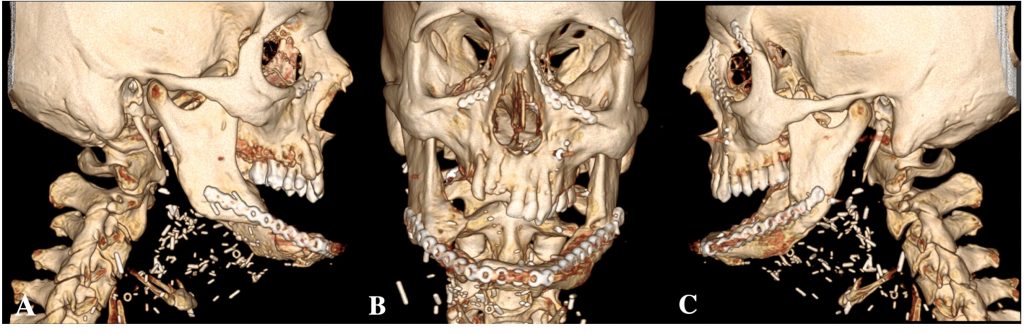

Additional workup included imaging of the face to determine extent of injury and included a CT head, CT maxillofacial, and CT cervical spine. CT findings are detailed based on anatomic location as follows and seen in Figure 2A-C:

CT findings in the mandible showed comminution of the anterior bodies greater in the left than right with symphyseal region present and absence of multiple bony fragments. On the left, there was a comminuted fracture of the posterior mandibular body and on the right, a nondisplaced fracture through the mandibular angle without dislocation of the condylar heads. Injury to the maxilla consisted of extensive comminuted fractures involving the bilateral hard palate, pterygoid plates and maxillary alveolar ridge; displaced fractures of the anterior, lateral and medial walls of the left maxillary sinus; and nondisplaced fractures of the lateral and medial walls of the right maxillary sinus. The nasal septum and base were also noted to have fractures. There was partial opacification of the bilateral maxillary and ethmoid sinuses consistent with trauma. Orbital involvement included a nondisplaced fracture of the lateral wall of the left orbit. A mildly diastatic fracture of the base of the left nasal bone and a mildly displaced fracture of the posterior left zygomatic arch were identified. The globes appeared grossly intact with proptosis but without evidence of intraorbital masses or hematomas. The craniocervical junction and vertebral alignment were intact with no acute fractures.

Pre-operative 3D CT Max/Face lateral right, anterior, and lateral left views showing extent of bony defects.

Plan:

The goal of treatment for this patient was to first explore and debride so that a clear assessment of the extent of injury could be completed. After this, the reconstructive plan was designed using virtual surgical planning (Figure 4A-F) and utilized a left free fibular flap to the mandible for bony reconstruction and a skin paddle for the soft tissue in the floor of the mouth. However, after a prolonged course involving an attempted salvage procedure with venous grafting, there was flap necrosis and removal. An alternative reconstruction plan was designed and completed using a chimeric scapular fascio-cutaneous flap and scapular bone free flap for anterior mandibular reconstruction.

Expertise Needed:

Plastic surgeon with experience in facial trauma and soft tissue injury was required for this case.

Treatment:

Initial treatment began with washout and debridement with wiring of the lateral maxillary and mandibular fragments together. All non-viable tissue was debrided, as well as removal of all bullet fragments. The posterior pharynx was closed with 3-0 chromic sutures and the maxillary segments were wired together to attempt to re-establish bony continuity, but due to the size of the defect a large palatal fistula was left. In the mandible, 24 gauge wire was used to bridle wire the segments of mandible, leaving behind periosteum and soft tissue to preserve blood supply for the future free fibular flap. The base of the mouth was closed with 3-0 vicryl and 3-0 chromic sutures, and the facial skin and lip closed with 4-0 monocryl and 5-0 nylon sutures. Post-operative closure shown in Figure 4A.

This initial procedure was closely followed by several subsequent debridements as well as open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of the left naso-orbital ethmoid fracture (Markowitz type 1), left zygomaticomaxillary fracture, right orbital rim fracture, open reduction and placement of mandibular reconstruction bar (Figure 4B), as well as extensive complex wound closure of the oral mucosa and face. There was a small area on the lower chin that was left open due to increased skin tension, seen in Figure 4C.

Figure 3A showing post-operative wounds after initial surgical procedure. Figure 3B demonstrates intraoperative placement of mandibular reconstruction bar. Figure 3C demonstrates post-operative results with open defect in the lower chin.

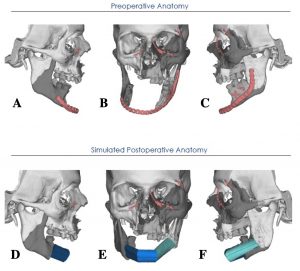

The reconstructive plan was designed using virtual surgical planning as seen below in Figure 4 and utilized a left free fibular flap to the mandible for bony reconstruction and a skin paddle for the soft tissue in the floor of the mouth. Intraoperative planning photos are shown below in Figure 5A-C.

Figure 4A-C showing preoperative anatomy. Figure 4D-F showing virtual simulated post-operative anatomy with utilization of a fibular flap for mandibular reconstruction.

Figure 5A shows intraoperative planning for fibular grafting and skin paddle design. Figures 5B and 5C demonstrate proposed recipient sites and placement of bone graft.

The face was debrided and washed out, and vessels on the right side of the face were prepared simultaneously with fibular flap preparation. The flap harvest began with creating of a 8x22cm skin flap centered over the posterior intermuscular septum, roughly 20% larger than the 6x18cm defect in the floor of the mouth. The fibular bone graft was then prepared, paying close attention to the superficial peroneal nerve and common peroneal artery. Once the bony segment was removed, the peroneal artery and peroneal venae comitantes were clipped proximally and divided. The fibular segment was then transected using the KLS Martin, ensuring protection of the peroneal pedicle. The fibula was then secured to the reconstruction plate using monicortical screws to ensure that there was not damage to the vascular pedicle. The right and left neck sites were then prepared; however, there was inadequate arterial inflow on the left that required a vein graft harvested from the retromandibular vein on the right and anastomosed in a reverse fashion to the right facial artery under the microscope. The distal end of the vein graft was then anastomosed to the peroneal artery of the fibular flap using 8-0 Nylon sutures. Once arterial inflow was established, the venous anastomoses were completed between one of the venae comitante of the peroneal vein to the previously identified vein in the left neck. The skin paddle was then inset to the base of the tongue and bilateral buccal mucosa. The skin paddle was then wrapped over the top of the reconstruction bar and sutured to the buccal mucosa of the lip. A small skin paddle was brought and left on the chin for monitoring purposes, as well as to avoid compression during closure of the anastomoses. The initial flap was viable with good perfusion for 72 hours; however, late flap failure occurred secondary to thrombosis of vein graft. Fibular free flap was removed and secondary reconstruction was planned using an osteocutaneous scapular flap for anterior mandibular reconstruction, as drawn below in Figure 6.

Intraoperative planning for scapular flap.

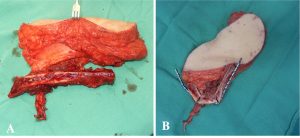

The previous flap sites were re-opened, and the neck defect recreated to identify the vascular supply for free tissue transfer. The mandibular reconstruction bar was removed in preparation for tissue transfer, and the bony layer was determined to require three limbs; 2.75cm for the central limb, 2.8cm for the right limb to the symphysis, and 5cm on the inner layer from the symphysis to the left angle. The oral floor defect was 14x8cm, and the external defect for the skin would require another 7cm in length. The scapular fasciocutaneous flap was designed to be 21x8cm with bony length of 10.55cm. The flap harvest was prepared using the previously described dimensions, centered over the midline of the perforating vessels for the scapular branch into the triangular space. The thoracodorsal branch coming off the latissimus into the subscapular system and the parascapular branch were then clipped and divided, as were the vena comitantes of the flap. The bone graft was then harvested with a 2cm width of bone along the lateral border of the scapula for approximately 14cm in length. The thoracodorsal artery and vein were similarly clipped and divided and the osteotomies completed using previous virtual surgical planning template. The reconstruction bar was secured to the scapular segment and the chimeric flap was then inset.

Figure 7A demonstrates the flap after harvest ex-vivo. Figure 7B shows bone graft once fitted with mandibular reconstruction bar.

It was clear once the fasciocutaneous portion was oriented over the reconstruction bar that there would not be clear apposition of the lip elements, seen in Figure 8B. The flap was then inset from the oral mucosa to the subcutaneous tissue of the flap to recreate the inner lining of the mouth and established adequate inset for microvascular anastomosis. The subscapular artery was anastomosed to the superior thyroid artery despite significant vessel mismatch. The venous anastomosis was performed from the subscapular vein to the facial vein and determined adequate perfusion. The right lip inset was completed with roughly 5cm of distal flap removed.

Figure 8A is intraoperative photo showing the defect once closed, with defect in lower lip apposition. Figure 8B shows healed post-operative results with bulk of fasciocutaneous flap demonstrated.

The patient then underwent surgery to debulk and revise the scapular fasciocutaneous paddle, repair of a persistent palatal fistula, and creation of labial buccal sulcus with full thickness skin grafting from the left medial arm (Figure 9A-C.)

Figure 9A demonstrating persistent palatal fistula. Figure 9B shows intraoperative definition of labial buccal sulcus. Figure 9C showing healed postoperative changes to the buccal sulcus.

Follow Up:

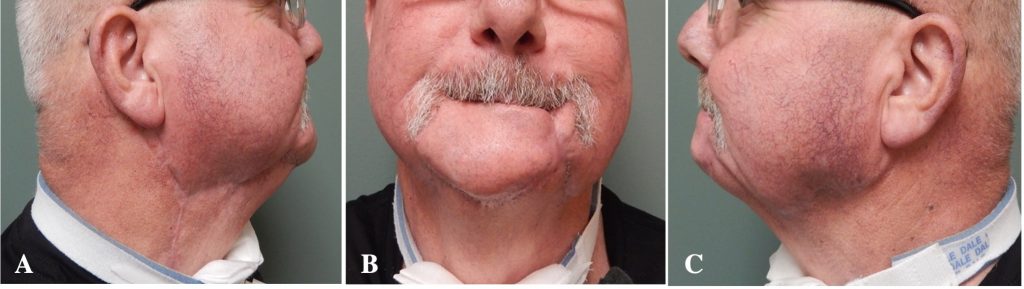

The patient was followed for more than two years with demonstration of reasonable oral competence, re-establishment of mandibular projection, and overall high patient satisfaction. The following postoperative photos are the completed result one year after the initial injury (Figure 10). The post operative CT findings are shown two years after initial injury in Figure 11, with stable postoperative changes of surgical fixation.

Figure 10A-C showing postoperative results 1 year after injury; right lateral, anterior, and left lateral respectively.

Figure 11A-C showing postoperative 3D CT Max/face with bony results 2 years after injury; right lateral, anterior, and left lateral respectively.