Ulcer from Radiation Induced Flap Necrosis

History:

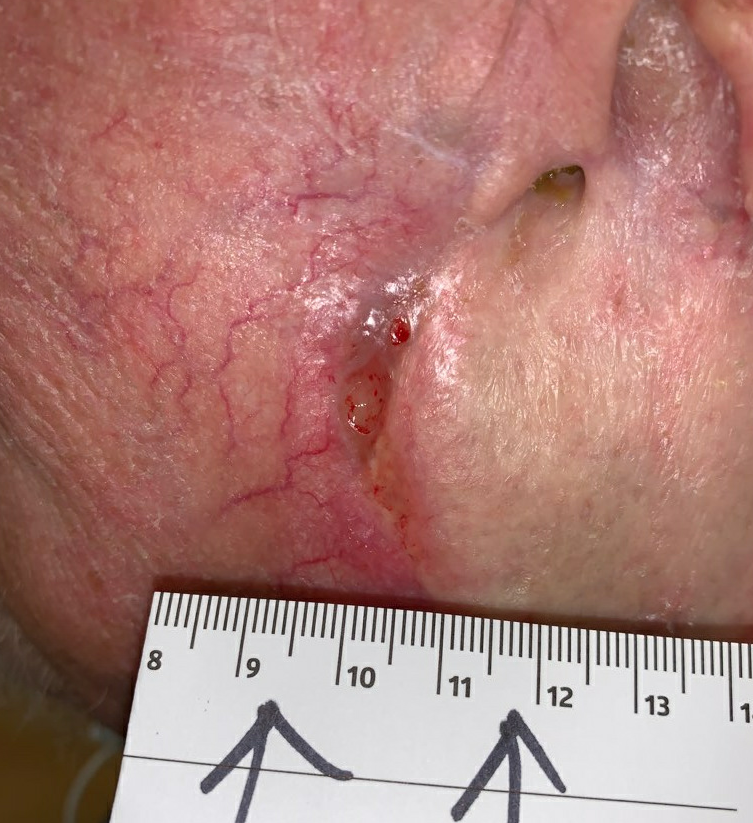

Original ulcer of left ear on presentation

S/p debridement at first visit

We performed a debridement of the necrotic tissue and eschar, resulting in the ulcer shown in the above right image. We prescribed local wound care with Dakins 0.0125% soaked gauze sponges to soak the wound at home prior to each dressing change, which we instructed the visiting wound nurses how to perform. We prescribed a dressing consisting of Gentamycin ointment and calcium alginate with an absorptant dressing, which we instructed to be changed 3x weekly. Over the course of the next month, he had gradual healing of his ulcer, requiring only one additional course of oral antibiotics. During this time, we referred him to plastic surgery for consideration for left earlobe reconstruction.

3 week follow up

1 week follow up

When he was evaluated by the plastic surgeon, there was concern for missed malignancy, which prompted a second referral to dermatology to rule out malignancy. A biopsy was taken at the resulting dermatology visit, which revealed left ear and face moderately differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC). He was taken for surgical resection, and final pathology demonstrated moderately differentiated Stage 3 SCC (pT3CN0).

Post Operative Day 1 from his Moh’s Surgery for Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

His wound from the Mohs surgery was closed with only a small defect remaining at the cephalad aspect, near the anterior aspect of the remaining ear. This was meant to close by secondary intention, so as not to put undue tension on the surrounding facial skin. The defect did lead to a tunnel through subcutaneous tissue that was also not able to be reasonably closed at the time of surgery. This was packed with Mesalt gauze, then covered with a Calcium Alginate dressing with an ABD pad, as there was moderate serosanguinous drainage. Over the next 6 weeks, the tunnel enlarged and the wound separated from its previous surgical closure, we suspect secondary to tension from the surgical closure on the tissue, combined with his already delayed wound healing. We continued to employ antimicrobial and absorption dressings to assist in wound closure, with gradual progress.

2 Weeks Post Mohs, wound is separating, and tunnel is not resolving

3 Weeks post Mohs

While attempting to heal his facial wound, he was referred to radiation oncology for consideration for post-op radiation. An MRI was performed and reviewed, and there was some suspicion for an involved intra-parotid lymph node. To rule out retained nodal disease, a PET-CT was performed, and did demonstrate PET avidity, concerning for lymph node metastasis, without distant involvement. A punch biopsy of the lymph node in question did confirm SCC metastasis. After multidisciplinary discussion, he was recommended to undergo re-excision with parotidectomy and modified radical neck dissection. The reconstructive plan at the time of surgery was to include a fasciocutaneous Anterolateral Thigh (ALT) flap, to be performed at the time of oncologic resection.

Findings:

3 Weeks post op. ALT flap was 17x8cm.

He was seen again at our wound center 2 weeks later, and was found to have a small open wound at the posterior margin of the flap, but with healthy granulation tissue in the wound bed. We recommended a collagen based dressing for the open area, with aquaphor to be applied to the suture line on the rest of the flap. He was scheduled to start radiation therapy later that day (post-op week 5). Over the next several weeks, he tolerated radiation therapy, with minimal change to the wound at the posterior aspect of the ear.

5 weeks post-op, small open area at the posterior graft margin. 2.4 x 0.8 cm

Diagnosis:

Follow Up:

We followed up with him every 2 weeks after he started radiation therapy, and while he tolerated it well, he was noted on our 6 week follow up to have significant ulceration and necrosis of his ALT flap. A diagnosis of radiation necrosis with threatened ALT flap was made (flap necrosis), and he was immediately considered for Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT).

Necrotic ALT flap, Week 6 of Radiation Therapy.

Necrotic ALT flap, Week 6 of Radiation Therapy.

After evaluation by our wound care and hyperbaric physician, he was found to be a good candidate, and was started on HBOT that week, with a plan to undergo a total of 40 sessions in a monoplace chamber, with a total of 2 ATA of oxygen administered for 90 minutes at each session. He completed this course over the next 2 months, undergoing HBOT 5 days per week. This ultimately resulted in graft salvage, and complete wound healing.

After HBOT #8. Open ulcerations significantly smaller, much improved perfusion of the flap.

After HBOT #18. Wounds progressively smaller, good incorporation of flap tissue onto wound bed.

After HBOT#32

1 week after HBOT#40/40

4 weeks after completing HBOT

4 weeks after completing HBOT

Fully healed, 2 months after completing HBOT

Discussion:

This case illustrated several key concepts in wound healing. First, it emphasizes the need to involve consultants in cases that present atypically, and in cases where a patient’s ulcer does not heal the way it is expected to. When the wound was healing poorly with the chosen therapy, one had to consider the possibility that the primary diagnosis was incorrect or that a previous pathological process was not fully resolved. In this case, one contributing factor to the initial poor wound healing may have been unresected (and unidentified) local malignancy. Involvement of the Plastic Surgeon prompted re-investigation by Dermatology, during which the primary malignancy was found after an initial biopsy which did not demonstrate it. Their suspicion ultimately got this patient the necessary therapy. A second example of a missed finding in this case occurred with referral for post-operative radiation therapy, when the Radiation Oncologist suspected and confirmed lymph node and parotid gland involvement by local metastases. Fortunately, the care of the patient was a multidisciplinary effort, in part because of complex comorbidities.

This case also demonstrated the efficacy of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) for the treatment of flap necrosis. In this case, flap necrosis was caused by radiation therapy as part of a comprehensive oncologic treatment. Other potential causes of flap necrosis might have included compromised flap blood supply, poor wound bed preparation, technical errors in the creation, transfer or anastomosis of the flap or its blood supply, and infection.