Pyoderma Gangrenosum

History:

Findings:

Patient had area of devitalized skin with a purulent cavity. On palpation, we were able to express a purulent discharge from the two small open areas. There was a small area of erythema in the vicinity of the ulcer bed, suggesting localized wound infection rather than a larger cellulitis. As there was a purulent cavity, we performed an incision and drainage with a wound culture. The wound was then dressed with cadexomer iodine and an absorptive dressing to reduce the bioburden and control exudate.

Fig.1. Wound at presentation. Affected area: 17.5cm² with small open ulcers.

Differential Diagnoses:

Workup Required:

Plan:

Expertise Needed:

Follow Up:

Fig.2. Week 2: Larger affected area with mild purulent drainage. Affected area: 25cm²

Week 2.5: The area of erythema and induration had improved somewhat, and she was mildly less painful. We suspected our course of Ciprofloxacin was working, so it was continued. There was no identifiable fluid collection, but there was a small area of devitalized skin that was debrided with a curette. Due to discomfort with debridement, the debrided area was small.

Week 3: The affected area of skin was again larger, and there were more open ulcers within the affected skin, with increased purulent drainage. At this time we started to question whether the infectious etiology was the primary cause of the ulcer, as it seemed to be progressing in spite of multiple courses of antibiotics, including antibiotics validated by our previous sensitivity data. We therefore performed a 3mm punch biopsy of the affected skin as well as a wound culture. The wound culture was ultimately negative for any growth, and the pathology results from the skin biopsy showed nonspecific ulceration with reactive squamous epithelium, and nonspecific dermal infiltration of neutrophils. These results were ultimately too non-specific to be helpful. We also changed the dressing to Hydrofera Blue with Spandagrip for mild compression and moisture control, as well as the antimicrobial properties of Hydrofera Blue.

Fig.3. Increased ulceration and affected area. Affected area: ~39cm²

Week 3.5: She continued to complain of worsening pain and purulent drainage, and we recommended an inpatient admission to perform a more expedited workup, given the steady worsening of the ulcer and as-yet unclear etiology. She refused, preferring to continue local wound care and outpatient management. We discussed the case with the PCP, and suggested a workup for autoimmunity, which was begun with an ESR and CRP. We performed lower extremity venous duplex studies, which were negative for acute thrombus and venous insufficiency, and a lower extremity MRI, which showed nonspecific inflammation of the soft tissues without any identifiable fluid collections.

Fig.4. Week 3.5: Increased area of affected skin, violaceous skin with increasing ulceration. Affected area: ~50.4cm²

Week 4: Her ulcers continued to enlarge, and she still complained of pain in the ulcer bed and surrounding skin. She remained afebrile, and had no other signs of systemic illness. We noted that there was some necrotic tissue in and around her ulcer bed, so we performed a limited debridement of the necrotic tissue only. During the debridement, it seemed as though the necrotic tissue was firmly adherent to the underlying tissue, and did not separate easily as one would usually expect of necrotic tissue. We also received her ESR and CRP back from her PCP’s workup, they were mildly elevated at 55 and 6.08, respectively. We dressed the wound with cadexomer iodine and an ABD pad, applying some gentle compression. Given her continued worsening, we requested that she see a surgeon for operative debridement, as this would allow for removal of all necrotic tissue, and would provide a larger tissue sample than the previous punch biopsy. When she saw the surgeon a couple of days later, he also recommended admission for IV antibiotics and operative debridement, which she refused. She would only agree to outpatient debridement, so this was scheduled.

Fig5. Week 4: Enlarging ulcer down to subcutaneous tissue, necrotic skin at the upper edge. Ulcer area: 59.8cm²

Fig6. Week 4: S/p minimal debridement due to firmly adherent necrotic tissue

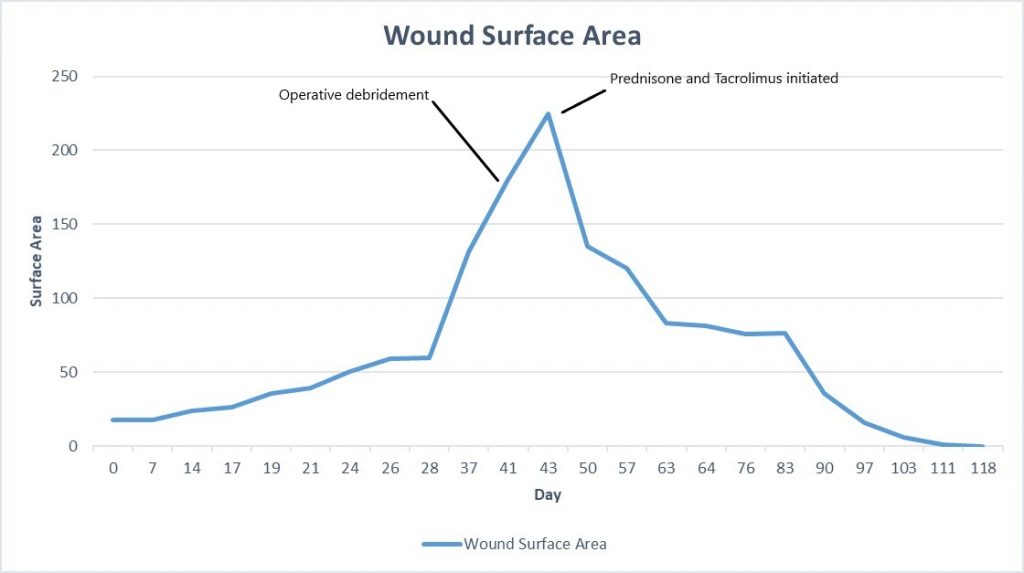

Week 4.5: She went for outpatient operative debridement in which all non-viable skin was sharply excised. Her post-operative skin defect was significantly larger, but clean throughout the ulcer bed.

Fig.7. Post-Operative photo, debrided down to subcutaneous tissue. Ulcer area: 131.2cm²

Week 5.5: On post-operative day 6 she followed up with us for the first time after her surgery. Her pain had improved significantly post-operatively, and the wound bed appeared clean. There was still a trace of violaceous coloration around the border skin. Her ANA had become available at this time, and it was positive (Titer 1:640, homogenous pattern), and her Rheumatoid factor was negative. Operative tissue pathology was not yet available, but based on the persistently violaceous border, and her positive ANA, we began to suspect that this was pyoderma gangrenosum. Her intraoperative cultures did grow 4+ Corynebacterium striatum. For her dressing, we selected silver hydrogel with a calcium alginate dressing, and mild compression. Given her positive ANA, we ordered an additional panel for autoimmune testing to further characterize her diagnosis. This panel later demonstrated all negative SSA/SSB antibodies, SCL-70 (scleroderma) antibodies, histone antibodies, dsDNA antibodies, CCP and SM + SM/RNP antibodies.

Week 6: At her next follow up there was significant exudate/slough in the ulcer base, and the periphery of the wound was erythematous and there were patches of newly necrotic skin. She was started on Bactrim for a possible infection, and a culture was performed, which ultimately grew 3+ Corynebacterium striatum. Her wound measured larger today, approximately 225cm², and given the rapid worsening after debridement, we suspected that this was a pathergy reaction, which is a hallmark feature of wounds with an autoimmune etiology, particularly pyoderma gangrenosum. We started her on topical Tacrolimus ointment, and discussed with her PCP, who started her on oral Prednisone, 20mg daily.

Fig.8. Week 6: Exudate/slough intermixed with scant granulation tissue in the ulcer bed, with new area of necrosis. Ulcer area: 225cm²

Week 6.5: She followed up with us again 3 days after starting her oral Prednisone and topical Tacrolimus, and her pain had completely resolved. The ulcer was also visibly improved, with more robust formation of granulation tissue, and small islands of re-epithelialization beginning to form. There was still some mild slough in the ulcer bed, but the drainage had nearly resolved. For her dressing, we continued a base layer of Tacrolimus ointment, followed by Hydrofera Blue and Coflex lite (for mild compression).

Fig.9. After 3 days of Prednisone and Tacrolimus. No significant change in size, but healthier tissue in ulcer bed.

Week 7-8: Her wound remained painless, and it continued to make rapid improvement both in surface area of open ulcer as well as the health of the wound bed and skin edge. Given her diagnosis of Pyoderma, debridement was specifically avoided. She continued her Tacrolimus ointment and Oral Prednisone.

Fig.10. Ulcer is decreased in size, edges and ulcer base are healthier with good granulation and epithelial islands. Ulcer area: 94.7cm²

Week 10: Her ulcer continued to improve, and remains painless. She had begun to have some irritation from the Hydrofera Blue dressing, so it was switched to adaptic with calcium alginate, we continued the compression. During this time, we were trying to disturb the ulcer as little as possible, so her dressings were left in place between appointments. She had been following up with us twice weekly, but given how well she was progressing, we moved to weekly follow up. She started to wean her prednisone at this time as well, taking 10mg Prednisone daily.

Fig.11. Week 10: Beefy red granulation tissue covers the entire wound bed, large patches of epithelialization. Ulcer area: 75.5cm²

Week 11-14: Her wound continued making great progress, and she was now fully weaned from her oral Prednisone. We continued using topical Tacrolimus, and suspect that her wound will heal without further intervention.

Fig.12. Week 11. Ulcer area: ~55cm²

Fig.13. Week 12. Ulcer area: 35.5cm²

Fig.14. Week 13. Ulcer area: 16cm²

Fig.15. Week 14. Ulcer area: 5.75cm²

By week 15, her ulcer had fully healed with complete re-epithelialization. We discharged her from our wound clinic, and instructed her to continue her topical tacrolimus for an additional 2 weeks to prevent the ulcer from recurring while her new skin was still immature. She was also counseled to keep the freshly healed skin protected from the sun, by wearing long pants when possible, or at least applying sunscreen when outside. She continued to do well, and had no recurrence of her ulcer.

Fig16. Week 15: Fully healed

Discussion:

This case highlightsd the importance of considering autoimmune etiologies in wounds that are not progressing well with initial therapies. Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG) is frequently underrecognized in clinical practice, and there is often a significant delay prior to establishing PG as the diagnosis and starting appropriate therapy. Perhaps we should have considered PG much earlier in this patient, given her history of a wound on her hand that healed with steroids. PG is associated with other autoimmune/systemic conditions in about 50% of patients, especially inflammatory bowel disease in about 30% of cases¹ (e.g. Crohns Disease and Ulcerative Colitis), as well as seronegative arthritis. Had this patient been younger, and had she not already undergone multiple negative screening colonoscopies, we would have referred her for colonoscopy to evaluate for inflammatory bowel disease, even if she did not meet other criteria for colorectal cancer screening. It is interesting and relevant to note that in cases of ulcerative colitis with concurrent PG, the skin lesions frequently resolve after total proctocolectomy.

Another key learning point from this case regards the Pathergy phenomenon, which describes an acute worsening of a wound after mechanical trauma. This can be seen with both operative debridement and wound biopsy, and is a feature of Pyoderma Gangrenosum as well as the ulcers prominent in Behcet Syndrome (an autoimmune vasculitis disorder with prominent muco-cutaneous ulcers). Pathergy is originally described in association with the Pathergy Test, in which the skin is pricked with a 20 gauge needle, and the eruption of a papular or pustular lesion results at the test site within 48 hours in a positive test. This test is rarely performed as it was initially described, and so the term ‘Pathergy’, is now used colloquially by many physicians to describe an abrupt worsening of a wound after biopsy, debridement or surgery. In the above case, the suggestive feature of pathergy was purulence and skin edge necrosis after her surgical resection.